Hurricane Lee has carved out its long-awaited right turn and is now swinging northward toward a landfall expected to occur in eastern New England or Atlantic Canada this week. Lee is predicted to be a hurricane until hours before it reaches the coast, and it will most likely come ashore as a powerful post-tropical storm with high winds capable of bringing down trees and power lines across a widespread area. Lee will also dump torrential rains across the region, which will likely cause dangerous flash flooding in a region coming off one of its wettest summers on record.

As of 2 p.m. EDT Wednesday, Lee had finally weakened below major hurricane status, with top sustained winds of 110 mph and a central pressure of 952 mb. Lee was centered about 1,015 miles south of Nantucket, Massachusetts, headed north-northwest at an accelerated pace of 9 mph. Continued weakening to Category 1 strength is expected through Friday because of cooler waters and increased wind shear.

Track forecast for Lee

The large-scale outlook for Lee’s movement has changed little. Lee has made its northward turn as a result of the influence of an upper trough over eastern North America. Forecast models are unified in a mostly northward track and acceleration of Lee through the rest of the week, resulting in a landfall between Cape Cod, Massachusetts, and western Nova Scotia this weekend. If Lee tracks on the slower end of the model projections, it will tend to go more to the west, near Cape Cod. If Lee moves faster, a more easterly track nearer to the U.S.-Canada border is likely. But given Lee’s very large wind field, with tropical storm-force winds that span a distance of over 500 miles, the entire coast from eastern Massachusetts to central Nova Scotia is likely to experience tropical storm conditions this weekend, regardless of Lee’s exact landfall location.

Storm surge

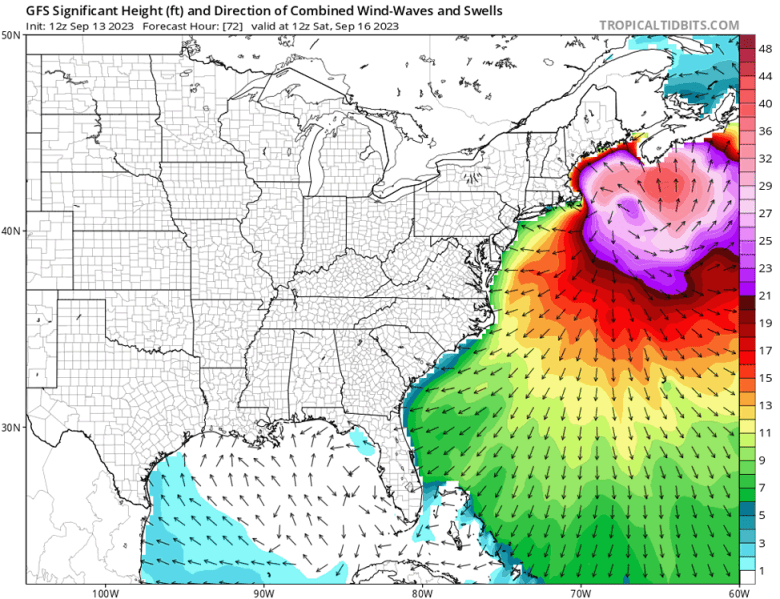

Lee’s large size will make it a more formidable storm surge threat than its maximum sustained winds would suggest, particularly since the surge will have very large waves on top of it. Fortunately, the phase of the moon will not be producing unusually high tides this weekend; the highest tides of the month at Cape Cod, Massachusetts, begin occurring on September 26. However, the timing of Lee’s arrival with respect to high tide is crucial, since the range between high tide is very large in this part of the world. Tidal range at Boston is about nine feet; the maximum storm surge flooding there is likely to occur near the high tide cycle around 1 p.m. EDT Saturday. At Eastport, Maine, on the Canadian border, the tidal range is about 18 feet; the maximum storm surge flooding is likely to occur near the high tide cycle at 12:31 p.m. EDT Saturday and potentially during the 12:48 a.m. EDT Sunday high tide as well.

As usual, the highest storm surge will occur near and to the right of where the center makes landfall, with western Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and eastern Maine at highest risk. The National Hurricane Center, or NHC, has not yet released any storm surge forecast numbers, but judging from past storms of similar intensity that have hit this area, plus the NHC Storm Surge Risk Maps for a Category 1 hurricane, two to three feet of storm surge flooding above normally dry ground could occur in these areas, if Lee hits at high tide. The coast of Maine is quite rocky with only a few low-lying areas, so storm surge damage should not be extreme there.

The counter-clockwise circulation of Lee will also pile up a significant storm surge in the Gulf of Maine to the north of Lee, and this surge will get funneled southward past Boston into the northern portion of Cape Cod, where the small Massachusetts communities of Rock Harbor, East Brewster, East Dennis, East Sandwich, and Barnstable will likely see damaging coastal flooding. Since Lee will be weakening as it heads north, the greatest U.S. coastal damage from the storm could well be along the north shore of Cape Cod, not to the right of where the center makes landfall.

A very large hurricane

Lee is very impressive in size, with hurricane-force winds that extend out up to 115 miles from the center. On Tuesday evening, hurricane-force winds extended out even farther, up to 125 miles. In the HURDAT2 database, which has size information for named Atlantic storms beginning in 2004, only five other hurricanes have been this large. The size champion is Hurricane Sandy of 2012, which had hurricane-force winds that extended out up to 205 miles from its center in one quadrant (the northeast side). The other storms as large as Lee were Hurricane Epsilon of 2020 (max hurricane-force wind radius of 160 miles), Hurricane Lorenzo of 2019 (150 miles), Hurricane Martin of 2022 (140 miles), and Hurricane Ike of 2008 (125 miles).

Lee’s tropical storm-force winds extend out up to 240 miles from the center. This is less than half of the record held by Hurricane Sandy: 550 miles. Second place is held by Hurricane Teddy of 2020 (540 miles), and third place is jointly held by three storms from 2020: Hurricane Martin, Hurricane Nicole, and Hurricane Ian, which all had tropical storm-force winds that extended out 480 miles from the center.

As of midday Wednesday, the National Hurricane Center was projecting 30% to 50% probabilities of tropical-storm-force winds (sustained at 39 mph or more, with higher gusts) over southeastern Massachusetts and southeastern Maine, with the highest odds near the coast. The center stressed that the wind speed probabilities beyond 36 hours in its text product and graphics are likely underestimating the risk of those winds occurring. This is because the forecast wind field of Lee is considerably larger than average compared to the wind field used to derive the wind speed probability product.

How did Lee get so big?

Lee has gained its large size from a combination of factors.

- The African tropical wave that Lee got its start from was large.

- Lee traversed record-warm ocean waters.

- Lee got very intense, reaching Category 5 strength.

- The relatively slow forward speed of the hurricane allowed it to undergo multiple eyewall replacement cycles (three so far), which acted to spread out a hurricane’s winds over a larger area.

- Lee’s northward path. As storms move towards Earth’s poles, they acquire more spin, since Earth’s rotation works to put more vertical spin into the atmosphere the closer one gets to the pole. This extra spin helps storms grow larger, and we commonly see hurricanes grow in size as they move northwards, as Lee is doing now.

- Interaction with a trough of low pressure at landfall. This hasn’t happened yet, but when Lee approaches landfall on Friday, it will interact with a trough of low pressure and become an extratropical storm. The nature of extratropical storms is to have a much larger area with strong winds than a hurricane does, since extratropical storms derive their energy from the atmosphere along a frontal boundary that is typically many hundreds of miles long.

Margot to loiter over the central North Atlantic for days to come

Harmless Hurricane Margot will be prowling the remote central North Atlantic for some time. At 11 a.m. EDT Wednesday, Margot’s sustained winds were at their peak so far, 90 mph, toward the high end of the category 1 range. Much like its cousin Lee farther west, Margot was exhibiting a double eyewall structure. While Lee chugs northward, Margot will be increasingly stuck within the Azores-Bermuda High helping to steer Lee. Forecast models, including the European (see Tweet below), suggest that Margot will wander for multiple days.

Sea surface temperatures of 27-28 degrees Celsius (81-82 degrees Fahrenheit) and moderate wind shear will allow Margot to maintain most of its strength over the next couple of days. Eventually, upwelling of cooler water will hasten Margot’s weakening, especially since there is little deep oceanic heat content in the area. At some point next week, Margot may get hauled toward Europe, perhaps accompanied by the remnants of Lee.

Invest 97L could be a tropical storm by this weekend

A disturbance dubbed Invest 97L in the eastern tropical Atlantic, located several hundred miles west-southwest of the Cabo Verde Islands Wednesday afternoon, will likely become the next Atlantic system of interest. The disturbance had a moderate amount of spin and was generating heavy thunderstorms that were becoming increasingly well organized, as seen on satellite images. The system also had a very moist midlevel atmosphere (relative humidity 75-80 percent) nurturing the showers and thunderstorms.

As it moves west-northwest to northwest over the next several days, 97L is predicted to experience only light to moderate wind shear (5-15 knots), and it will move over sea surface temperatures of 29-30 degrees Celsius (84-86°F) with increasingly warm deep-ocean waters. In its 2 p.m. EDT Wednesday tropical weather outlook, the National Hurricane Center gave two-day and seven-day odds of 70% and 90% that 97L would strengthen into at least a tropical depression. Once a closed center of circulation forms, it may only take a day or two for 97L to become a tropical storm. The next name on the Atlantic list is Nigel.

Ensemble models are in strong agreement that steering currents will take 97L toward the northwest into early next week, angling toward the weakness produced by Margot in the Azores-Bermuda High. If so, the system would most likely avoid the Lesser Antilles and Caribbean. Systems that far north typically recurve before approaching North America, and this is suggested for 97L by most of the current model ensemble members. However, given that any westward bend or ultimate recurve is a week or more away, it is too soon to predict the longer-term fate of 97L with confidence.

Website visitors can comment on “Eye on the Storm” posts (see comments policy below). Sign up to receive notices of new postings here.